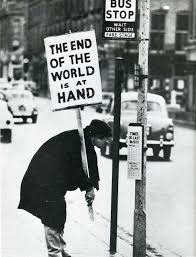

Americans rush to defend free market capitalism’s elimination of the “public good,” to our own detriment. Why do we do that?

The short (but complex) answer is that free market capitalism has become the dominant American economic and social ideology, and there’s no place for an egalitarian notion like the public good in its competitive culture.

The X Factor

Economic data suggest we’re in the advanced stages of competitive, zero sum capitalism’s systematic extermination of the public good. But a surprising X Factor could help reverse this trend.

What is it?

Happiness.

Let’s take a look….

It Wasn’t Supposed to Work That Way

Free market godfather Milton Friedman famously said that “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” That was free market capitalism’s bold theory: there was no need to import the European ideal of safeguarding the public good; instead, you could give capitalism free reign and everyone would benefit — and no need for social democracy’s clumsy bureaucracy.

We Yanks thought we could do better, but we were wrong, and we were wrong because we were duped. Free market ideology staked its claim as a science, but it wasn’t — it was an ideology, a religion. For it to work, you had to believe, and to aggressively demonstrate your commitment to its ideal or a pure capitalist state.

We heard the call to discipleship, but we still remembered that the compassionate social programs of the Roosevelt New Deal, engineered by Keynesian economic theories of government intervention, had bailed us out of the Great Depression and fueled a startling worldwide recovery from the rubble of two world wars – a recovery that lifted all economic fortunes and established the middle class as the mainstay of socio-economic stability.

But that wasn’t enough for the free market idealists who had already been theorizing and strategizing at their Mont Pelerin Society meetings in the mountains of Switzerland. But their time had not yet come, and they waited, constructing mathematical models that proved they were right — in theory, at least, even though they were untested empirically — until history finally handed them their chance.

European democratic socialism’s reputation had been compromised by the abuses and miseries of its far distant relative, Soviet Communism. The free marketers must have known, but the rest of us didn’t see that they weren’t the same thing, and when the Berlin Wall came down, we celebrated the end of the Cold War by declaring capitalism the victor, and then we set out to cleanse the world of our defeated “socialist” foe. While a new class of Russian opportunists became billionaires by scavenging former state-owned assets at below bargain basement prices, Bill Clinton and Tony Blair led the charge to purge their respective countries of any taint of vanquished socialism, which they and everyone equated with Communism. National and corporate leadership snatched the keys to free capitalism’s shiny new muscle car and went peeling out, careening donuts in the cities and shredding fragile tundra in the mountains. The American way of rugged individualism and upward mobility and anybody can make it here if they have enough gumption and are willing to work hard resounded through the halls of government on both sides of the aisle on both sides of the Atlantic, and we routed the welfare queens out from in front of their TVs, put food stamps slackers back to work, created the Incarceration State, and savaged the environment… all to shouts of “workfare!” – a new translation of “hallelujah!”

Competitive capitalism became the new state religion — its competitive capitalism campaign slogans became its scriptures, and its entrepreneurial heroes as iconic as dear old Betsy Ross and her flag, and it became culturally criminal to deface them. Cultural myths and icons grow to sacred stature, snuffing out discourse and banning dissent. That doesn’t ensure success, but it does mean that the electorate will still trudge dutifully to the polls and ante up for another round, long after it has become obvious to anyone with ears to hear and eyes to see that the ideology hasn’t delivered on its promise. And thus the American electorate has done for the past four decades, believing with fundamentalist zeal in Friedman’s promise of economic utopia until today we’re left with socio-economic structures of inequality matched only by the days of the French Revolution, the Robber Barons, and the Roaring 20’s.

It wasn’t supposed to work that way, but it did.

The Unconscious Underbelly

Ideologies originate in the neural pathways of the people who create them, and spread from brain to brain until enough brains have the same wiring and, by a process known as “emergence,” they take on a life of their own in the institutions they create and sustain.[1]

Of course, most people don’t go around thinking about how their neural pathways process free market ideological biases. Instead they respond to the issues – politicians urging them to reject the public good in favor of the chance to do have it your way and forget the deep state and its non-elected manipulating – and never mind that the public good that you’re voting out of existence includes your own.

We do some things consciously, with intent and purpose, but we do much more for reasons we’re not in touch with, or for no reason at all – the latter two driven by unconscious impulses derived from the cultural biases wired into our brains. There is, for example, ample research to suggest an additional endemic cultural factor that helps to explain why we support elected officials and their economic agendas even when doing so is against our own best interests. That factor is culturally embedded racism.

“One question that has troubled Democrats for decades is freshly relevant in the Trump-McConnell era: Why do so many voters support elected officials who are determined to cut programs that those same voters rely upon?

“There is, however, one thread that runs through all the explanations of the shift to the right in Kentucky and elsewhere. Race, the economists Alberto F. Alesina and Paola Giuliano write, ‘is an extremely important determinant of preferences for redistribution. When the poor are disproportionately concentrated in a racial minority, the majority, ceteris paribus, prefer less redistribution.’

“Alesina and Giuliano reach this conclusion based on the “unpleasant but nevertheless widely observed fact that individuals are more generous toward others who are similar to them racially, ethnically, linguistically.”

“Leonie Huddy, a political scientist at the State University of New York — Stony Brook, made a related point in an email: ‘It’s important to stress the role of negative racial and ethnic attitudes in this process. Those who hold Latinos and African-Americans in low esteem also believe that federal funds flow disproportionally to members of these groups. This belief that the federal government is more willing to help blacks and Latinos than whites fuels the white threat and resentment that boosted support for Donald Trump in 2016.

“In their 2004 book, “Fighting Poverty in the U.S. and Europe: A World of Difference,” Alesina and Edward L. Glaeser, an economist at Harvard, found a pronounced pattern in this country: states ‘with more African-Americans are less generous to the poor.’”[2]

Culturally embedded racism is the same trend that developed the “Welfare Queen” stereotype, which was shaped – as all stereotypes are — from the twisted truth of a notorious 60’s case of welfare fraud that became the standard citation for the free market’s case against the social safety net.

It Wasn’t Supposed to Work That Way, Part 2

If you’re going to have a public good, you need to have a government that supports it. Theoretically we do: the USA’s republican form of government isn’t a “pure democracy” –instead we elect people to represent us, trusting that they will act in our best interests, which are represented by the word “public” right there in its name.[3]

Republic (n.): c. 1600, “state in which supreme power rests in the people via elected representatives,” from Middle French république (15c.), from Latin respublica (ablative republica) “the common weal, a commonwealth, state, republic,” literally res publica “public interest, the state,” from res “affair, matter, thing” (see re) + publica, fem. of publicus “public” (see public (adj.)). Republic of letters attested from 1702.[4]

Publica (the people, the state) + Res (affair, matter, thing) = “the people’s stuff.” The republican state holds the people’s stuff in trust, and its elected representatives, as trustees administer it for the public benefit. A more elegant term for “the public’s stuff” is “commonwealth”:

Commonwealth (n.): mid-15c., commoun welthe, “a community, whole body of people in a state,” from common (adj.) + wealth (n.). Specifically “state with a republican or democratic form of government” from 1610s. From 1550s as “any body of persons united by some common interest.” Applied specifically to the government of England in the period 1649-1660, and later to self-governing former colonies under the British crown (1917).[5]

The res publica is made up of those goods, services, and places that everybody is entitled to simply by being a citizen. Once the res publica is legislated into being, someone has to administer it in trust for the public’s benefit. If you can’t administer public goods, there’s no point in creating them in the first place, and free market ideology emphatically doesn’t want government to do either– even if that government is supposedly a republican one.

Superstar Italian-American economist Mariana Mazzucato (The Times called her “the world’s scariest economist”) describes how limited government has eliminated the commonwealth from policy-making:

“[Government is] an actor that has done more than it has been given credit for, and whose ability to produce value has been seriously underestimated – and this has in effect enabled others to have a stronger claim on their wealth creation role. But it is hard to make the pitch for government when the term ‘public value’ doesn’t even currently exist in economics. It is assumed that value is created in the private sector; at best, the public ‘enable’ [that privately created] value.

“There is of course the important concept of ‘public goods’ in economics — goods whose production benefits everyone, and which hence require public provision since they are under-produced by the private sector.

“… the story goes [that] government should simply focus on creating the conditions that allow businesses to invest and on maintaining the fundamentals for a prosperous economy: the protection of private property, investments in infrastructure, the rule of law, an efficient patenting system. After that, it must get out of the way. Know its place. Not interfere too much. Not regulate too much.

“Importantly, we are told, government does not ‘create value’; it simply ‘facilitates’ its creation and — if allowed — redistributes value through taxation. Such ideas are carefully crafted, eloquently expressed and persuasive. This has resulted in the view that pervades society today: government is a drain on the energy of the market, and ever-present threat to the dynamism of the private sector.”[6]

Ironically, while the ideal of limited government enjoys wide appeal, the actual reality has been the opposite: while the public good has been cut and slashed, the size of federal government has burgeoned during the free market’s reign, as measured by any number of economic markers, including national debt, number of government employees and contractors, size of the federal budget, and government spending — especially on national security and the military, including what some are calling the “military welfare state.”

The Public Good Wish List

Thus free market ideology has destroyed as much republican government as it could, and driven the rest into hiding. But suppose both could be restored to their places at the economic policy conference table. Beyond “the fundamentals for a prosperous economy: the protection of private property, investments in infrastructure, the rule of law, an efficient patenting system,” what might be included in a restored commonwealth trust fund? Several online searches turned up a long and illuminating list of things that used to be considered part of the commonwealth trust portfolio, or that might be added to it:

- education

- news

- law

- governmental administrative functions

- healthcare

- childcare

- clean water

- clean air

- certain interior spaces

- certain exterior spaces — e.g. parks

- natural wonders

- shoreline and beaches

- mail and home/rural delivery service

- trash removal

- public toilets

- sewage processing

- protection from poverty – e.g., provision of food, clothing, and shelter

- affordable housing

- heat and lights

- streets, roads, highways

- public transportation

- freight shipping

- telephone and telegraph

- pest control

- use of public lands/wilderness access

- the “right to roam”

- the “right to glean” unharvested crops

- the right to use fallen timber for firewood

- security and defense

- police and fire

- handicapped access

Some people argue for the inclusion of additional, more contemporary items on the list:

- information

- internet access

- net neutrality

- open source software

- email

- fax

- computers

- cell phones

- the “creative commons” (vs. private ownership of intellectual property)

- racial, gender, national, and other forms of equality

- birth control

- environmental protection

- response to climate change

What’s Wrong With That List?

Turns out that certain of the things on that list might not technically qualify as public goods, but before we look at that, what was your response to the list? Did you find some items frivolous, maybe outrageous? Did you favor things that would benefit you personally over those that wouldn’t? Did some of the items make you want you to get on your moral high horse and ride? Probably you did all of that, because there will always be investments in the commonwealth trust portfolio that you don’t value for yourself. But that’s exactly the point: the commonwealth looks to the health of the whole, not what the rugged individual might be able to do for himself if everybody would just leave him alone.

This individual vs. group conflict enjoyed a respite when the neoliberal economics of the post-WWII years picked up the interrupted impetus of the prewar New Deal, creating as a result the halcyon days of the public good, with widely-shared benefits to the middle class and the American Dream of equal opportunity and upward socio-economic mobility. But when the recovery played out in the 70’s and was then replaced with the free market’s reign, the technicalities of what is public vs. private good became more important. Which is why, when you had those typical responses to the list – questioning this, preferring that — you were putting your finger precisely on several key and complex reasons why the public good is tricky to define and administer – complexities free market capitalism avoids by skewing the balance all the way to the private side of the balance. For example:

- “A public good must be both non-rivalrous, meaning that the supply doesn’t get smaller as it is consumed, and non-excludable, meaning that it is available to everyone.”[7] This is largely a matter of fiat: while many things on the list could be made to fit this requirement, they aren’t currently, thanks to the free market insistence on privatization, believing that will make everything optimally available. While phones and computer and internet access could be made free, open, and universal, trillions of dollars’ worth of private enterprise would have something to say about that.

- Public goods inevitably give rise to the “free rider problem,” defined as “an inefficient distribution of goods or services that occurs when some individuals are allowed to consume more than their fair share of the shared resource or pay less than their fair share of the costs. Free riding prevents the production and consumption of goods and services through conventional free-market To the free rider, there is little incentive to contribute to a collective resource since they can enjoy its benefits even if they don’t.”[8] Freeriding means public radio and TV can’t prevent people from enjoying their programming even if they don’t pony up during the annual fund-raising campaign.

- Government solves the free-rider problem by levying taxes to pay for public services – e.g., a special assessment to pay for sewer maintenance on your street. Only trouble is, “taxes” are fightin’ words – both in free market theory and generally for many if not most Americans. We’re stuck back at “taxation without representation” and “don’t tread on me” and “give me liberty or give me death” – if we don’t want it or can’t get it for ourselves, we’d rather go without it than pay taxes so that everybody else can have it.[9] Free market capitalism is okay with enough government to legislate itself into dominance, but then government needs to get out of the way.

- “Market failure”[10] is the key to the public goods door. It occurs when the free market doesn’t deliver. Free market capitalism relies on the common economic assumption that consumers acting rationally in their individual best interests will generate the optimal level of goods and services for everyone. This ideal is unrealized for the vast majority of things on the wish list, and giving it a boost requires a new configuration of what is properly a public or a private good.[11]

- Even if we put public goods in place to override free market failures, we’ll still face the “tragedy of the commons,” defined as “an economic problem in which every individual has an incentive to consume a resource at the expense of every other individual with no way to exclude anyone from consuming. It results in overconsumption, under investment, and ultimately depletion of the resource. As the demand for the resource overwhelms the supply, every individual who consumes an additional unit directly harms others who can no longer enjoy the benefits. Generally, the resource of interest is easily available to all individuals; the tragedy of the commons occurs when individuals neglect the well-being of society in the pursuit of personal gain.”[12] The tragedy of the commons is why beaches post long lists of rules: it may be a public place, but a raucous party can ruin it for everyone else who wanted a tranquil place for a beach read.

These issues are inescapable: if you want public goods, you need to deal with them.

“Homo Economicus”

The issue of market failure ought to be the easiest issue to tackle, since it is based on a long-discredited notion of the rational economic man – the assumption that people will act rationally in their economic dealings, and that “rationally” means in their own best interests. John Stuart Mill coined the term homo economicus to explain this economic behavior:

“Homo economicus, or ‘economic man,’ is the characterization of man in some economic theories as a rational person who pursues wealth for his own self-interest. The economic man is described as one who avoids unnecessary work by using rational judgment. The assumption that all humans behave in this manner has been a fundamental premise for many economic theories.”[13]

The idea has had its detractors:

“The theory of the economic man dominated classical economic thought for many years until the rise of formal criticism in the 20th century.

“One of the most notable criticisms can be attributed to famed economist John Maynard Keynes. He, along with several other economists, argued that humans do not behave like the economic man. Instead, Keynes asserted that humans behave irrationally. He and his fellows proposed that the economic man is not a realistic model of human behavior because economic actors do not always act in their own self-interest and are not always fully informed when making economic decisions.”[14]

Even so,

“Although there have been many critics of the theory of homo economicus, the idea that economic actors behave in their own self-interest remains a fundamental basis of economic thought.”[15]

Ayn Rand Would Have Approved

The concept of “homo economicus” captures the free market belief that the rigorous pursuit of self-interest improves things for everyone. It finds a philosophical ally in Ayn Rand’s “objectivism”:

“The core of Rand’s philosophy… is that unfettered self-interest is good and altruism is destructive. [The pursuit of self-interest], she believed, is the ultimate expression of human nature, the guiding principle by which one ought to live one’s life. In “Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal,” Rand put it this way:

‘Collectivism is the tribal premise of primordial savages who, unable to conceive of individual rights, believed that the tribe is a supreme, omnipotent ruler, that it owns the lives of its members and may sacrifice them whenever it pleases.’

“By this logic, religious and political controls that hinder individuals from pursuing self-interest should be removed.”[16]

Thus Ayn Rand became the patron saint of free market.

“’I grew up reading Ayn Rand,’ … Paul Ryan has said, ‘and it taught me quite a bit about who I am and what my value systems are, and what my beliefs are.’ It was that fiction that allowed him and so many other higher-IQ Americans to see modern America as a dystopia in which selfishness is righteous and they are the last heroes. ‘I think a lot of people,’ Ryan said in 2009, ‘would observe that we are right now living in an Ayn Rand novel.’”[17]

The X Factor: What Would be Wrong With a Little Happiness?

But you don’t need to be anybody’s patron saint to like the idea of the public good. You just need to be self-interested enough to want to be happy – or at least be envious of those who are.

Back to our Public Goods Wish List. Technicalities and difficulties of definition and administration aside, if we look at it from the perspective of “wouldn’t that be nice” there’s not a lot to dislike about it. While free market indoctrinated Americans seems to have a bad case of being right instead of being happy, the social democracies that feature the public good –whose citizens don’t seem to be so adverse to their own happiness — routinely score the highest in The World Happiness Report:

“Finland again takes the top spot as the happiest country in the world according to three years of surveys taken by Gallup from 2016-2018. Rounding out the rest of the top ten are countries that have consistently ranked among the happiest. They are in order: Denmark, Norway, Iceland, Netherlands, Switzerland, Sweden, New Zealand, Canada and Austria. The US ranked 19th dropping one spot from last year.”[18]

The capitalists who need our labor would do well to recall that happy workers are better workers – more loyal, productive, loyal, creative, innovative, and collaborative.[19] Further, as the following perspective on Switzerland shows, democratic socialism can still offer plenty of healthy capitalism:

“Like many progressive intellectuals, Bernie Sanders traces his vision of economic paradise not to socialist dictatorships like Venezuela but to their distant cousins in Scandinavia, which are just as wealthy and democratic as the United States but have more equitable distributions of wealth, as well as affordable health care and free college for all.

“There is, however, a country far richer and just as fair as any in the Scandinavian trio of Sweden, Denmark and Norway. But no one talks about it.

“This $700 billion European economy is among the world’s 20 largest, significantly bigger than any in Scandinavia. It delivers welfare benefits as comprehensive as Scandinavia’s but with lighter taxes, smaller government, and a more open and stable economy. Steady growth recently made it the second richest nation in the world, after Luxembourg, with an average income of $84,000, or $20,000 more than the Scandinavian average. Money is not the final measure of success, but surveys also rank this nation as one of the world’s 10 happiest.

“This less socialist but more successful utopia is Switzerland.

“While widening its income lead over Scandinavia in recent decades, Switzerland has been catching up on measures of equality. Wealth and income are distributed across the populace almost as equally as in Scandinavia, with the middle class holding about 70 percent of the nation’s assets. The big difference: The typical Swiss family has a net worth around $540,000, twice its Scandinavian peer.

“The real lesson of Swiss success is that the stark choice offered by many politicians — between private enterprise and social welfare — is a false one. A pragmatic country can have a business-friendly environment alongside social equality, if it gets the balance right. The Swiss have become the world’s richest nation by getting it right, and their model is hiding in plain sight.”[20]

Yes, the citizens of countries that promote the public good pay more taxes, but as this article[21] points out, that doesn’t mean the government is stealing their hard-earned money, instead it’s a recognition that paying taxes acknowledges what the national culture has contributed to their success. Meanwhile there’s still plenty of happiness to go around.

The X Factor, One More Time

It would take a lot to reclaim the public good from free market capitalism’s pogrom against it, and all appearances are that won’t happen anytime soon. But if it ever does, it could be a newly reinvented and revitalized homo economicus’ finest hour, motivated by the simple human desire to be happy.

Imagine that.

[1] For more on neuro-culture, see Beliefs Systems and Culture in my Iconoclast.blog.

[2] Why Don’t We Always Vote in Our Own Self-Interest? New York Times (July 19, 2018).

[3] Pure democracy — all those ballot initiatives — has joined republican lawmaking since California’s 1978 Proposition 13.

[4] Etymology Online.

[5] Etymology Online

[6] The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths (orig. 2013, rev’d 2018) See also The Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy (2018).

[7] Investopedia.

[8] Investopedia.

[9] This is a particularly thorny issue for philanthropy – see this article and that one.

[10] Investopedia.

[11] See Everyday Ethics: The Proper Role of Government: Considering Public Goods and Private Goods, The Rock Ethics Institute, University of Pennsylvania (Apr 15, 2015).

[12] Investopedia.

[13] Investopedia

[14] Investopedia

[15] Investopedia.

[16] What Happens When You Believe in Ayn Rand and Modern Economic Theory, Evonomics (Feb. 17, 2016)

[17] How America Lost Its Mind, The Atlantic (Sept. 2017)

[18] See the full list here. See also the corollary Global Happiness and Well-Being Policy Report – here’s the pdf version.

[19] See The Real Advantage of Happy Employees from Recruiter.com., also this re: an Oxford study: A Big New Study Finds Compelling Evidence That Happy Workers Are More Productive, Quartz at Work (Oct. 22, 2019)

[20] The Happy, Healthy Capitalists of Switzerland, The New York Times (Nov. 2, 2019).

[21] No It’s Not Your Money: Why Taxation Isn’t Theft, Tax Justice Network (Oct. 8, 2014). And for a faith-based perspective I’ve never heard from the religious right, see Faithfully Paying Taxes to Support the Common Good, Ethics Daily (April 12, 2018).